Cadiz provides

innovative

water solutions

Solutions

New climate realities require new and innovative solutions. When it comes to rain, snow and water supplies, extreme is the new normal. Adapting to extreme new weather patterns resulting from climate change means finding new ways to capture, conserve, store and transport water

Our Clean Water Solutions

Supply

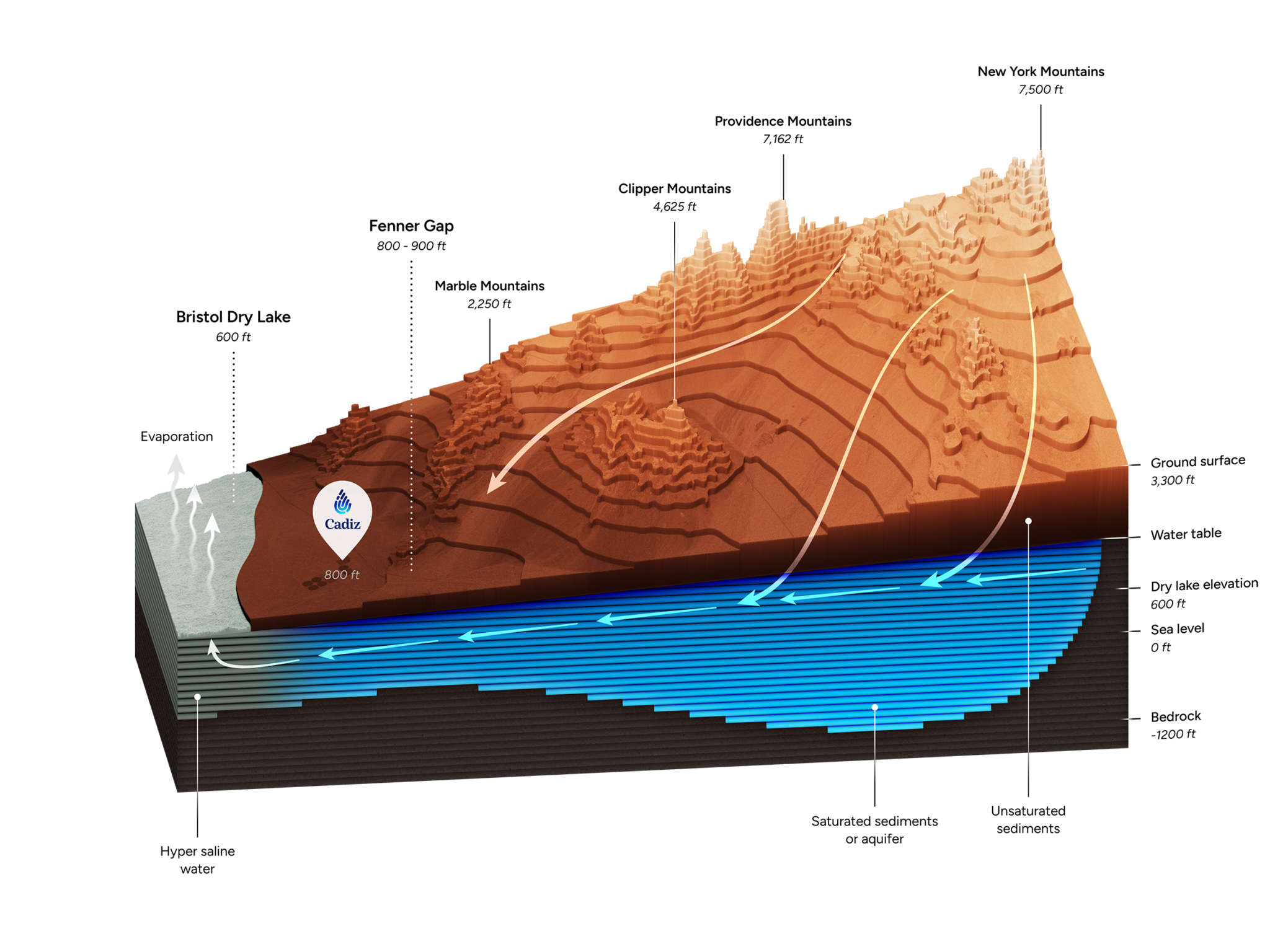

The Problem

Climate change has dramatically altered hydrologic cycles around the world. Unpredictable swings in weather patterns from extreme droughts to atmospheric rivers cause unreliable water supplies.

Our Solutions

New water supply generated by conserving existing groundwater before it is lost to evaporation and delivered to local communities for drinking water, groundwater replenishment and emergencies.

The Benefit

Reliable 50-year water supply fully permitted under a county approved sustainable yield plan; enough to serve over 1.2 million people annually.

Storage

The Problem

California’s snowpack is shrinking with more precipitation falling as rain and atmospheric rivers than snow. Our existing reservoirs and groundwater banks have limited ability to capture these storm waters.

Our Solution

Cadiz provides the largest new groundwater bank in Southern California with 1 million acre-feet of underground storage capacity, safe from evaporation.

The Benefit

Surplus water can be safely stored at Cadiz and withdrawn when needed, without loss to evaporation or risk of curtailment due to drought conditions.

Conveyance

The Problem

Our current water transportation network of canals and aqueducts was not designed for climate realities.

Our Solution

Repurpose existing pipelines originally built to transport oil to carry water to rural, poor and underserved communities in Southern California.

The Benefit

By renovating existing underground oil/gas pipelines to deliver water we expand needed critical water infrastructure faster, at lower cost and with less environmental impact.

Treatment

The Problem

Changes in natural sources and modern industrial practices continue to increase presence of groundwater contaminants that pose serious health risks.

Our Solutions

ATEC, a Cadiz Solution provides the most cost-effective, and versatile water treatment technology in the Western United States.

The Benefit

Our treatment technology is scalable making it an effective solution for residents of communities facing disproportionate risk of hazardous water as well as large municipality.

Expertise

The Problem

As our water challenges increase, we must continue finding and adopting efficient practices to conserve as much water as possible.

Our Solutions

Cadiz brings 40 years of experience with arid desert farming and groundwater management practices.

The Benefit

We can share what we’ve learned and help others adopt innovative practices for a more sustainable future.

Our Clean Water Solutions

New climate realities require new and innovative solutions. When it comes to rain, snow and water supplies, extreme is the new normal. Adapting to extreme new weather patterns resulting from climate change means finding new ways to capture, conserve, store and transport water

Learn & Explore

Supply

The Problem

Climate change has dramatically altered hydrologic cycles around the world. Unpredictable swings in weather patterns from extreme droughts to atmospheric rivers cause unreliable water supplies.

Our Solutions

New water supply generated by conserving existing groundwater before it is lost to evaporation and delivered to local communities for drinking water, groundwater replenishment and emergencies.

The Benefit

Reliable 50-year water supply fully permitted under a county approved sustainable yield plan; enough to serve over 1.2 million people annually.

Storage

The Problem

California’s snowpack is shrinking with more precipitation falling as rain and atmospheric rivers than snow. Our existing reservoirs and groundwater banks have limited ability to capture these storm waters.

Our Solutions

Cadiz provides the largest new groundwater bank in Southern California with 1 million acre-feet of underground storage capacity, safe from evaporation.

The Benefit

Surplus water can be safely stored at Cadiz and withdrawn when needed, without loss to evaporation or risk of curtailment due to drought conditions.

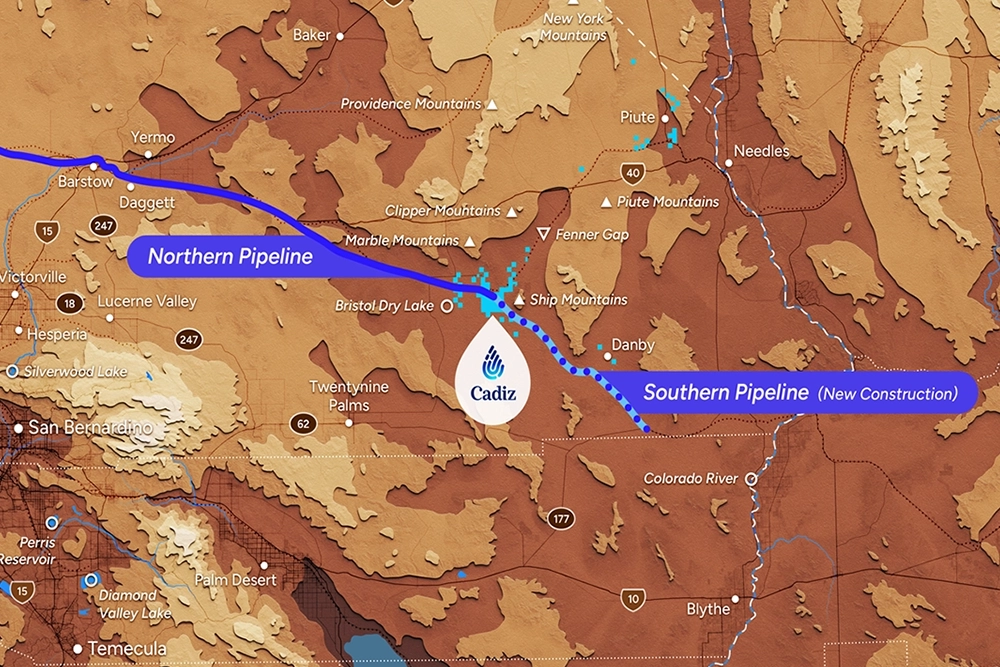

Conveyance

The Problem

Our current water transportation network of canals and aqueducts was not designed for climate realities.

Our Solutions

Repurpose existing pipelines originally built to transport oil to carry water to rural, poor and underserved communities in Southern California.

The Benefit

By renovating existing underground oil/gas pipelines to deliver water we expand needed critical water infrastructure faster, at lower cost and with less environmental impact.

Treatment

The Problem

Changes in natural sources and modern industrial practices continue to increase presence of groundwater contaminants that pose serious health risks.

Our Solutions

ATEC, a Cadiz Solution provides the most cost-effective, and versatile water treatment technology in the Western United States.

The Benefit

Our treatment technology is scalable making it an effective solution for residents of communities facing disproportionate risk of hazardous water as well as large municipalities.

Expertise

The Problem

As our water challenges increase, we must continue finding and adopting efficient practices to conserve as much water as possible.

Our Solutions

Cadiz brings 40 years of experience with arid desert farming and groundwater management practices.

The Benefit

We can share what we’ve learned and help others adopt innovative practices for a more sustainable future.